The Bird Story, Part 6

and, of course, links.

If you are new or forgetful, the Bird story starts here.

Both Bird and I saw Japan, nearly 150 years apart. Letter by letter, I followed Bird. She started in Tokyo, then traveled mostly on horseback through the countryside north of that city and up to Aomori, where she hitched a ride on a boat up to Hokkaido, the most northerly island in the chain. In Bird’s time, most of the population were Ainu, the indigenous people who were in the process of being subjugated to Japanese rule. Even now, most non-Japanese people don’t travel up to Hokkaido. In the 19th century, it was almost unheard of. She was the first European and the first woman to experience this part of this only recently opened country.

Bird didn’t travel alone, mind. At the start of her journey, she worked with an acquaintance at the British Consulate to hire an interpreter/fixer to smooth her path through the unbeaten (by a white person) terrain. Through that process, she found Ito, a 19-year old Japanese would-be dandy with a questionable past. The mis-matched pair would be fantastic fodder for a buddy comedy, if only Hollywood producers found the idea of a buddy comedy about a middle-aged matron marketable.

I finished reading Unbeaten Tracks in February 2020. The story was enjoyable enough. The pictures she painted about her Japan both tracked with what my experience had been and showed me a wildly strange place. After turning the last page — on it, Isabella broke down how much she spent at each city, just in case someone wanted to recreate her trip — I put the book on my desk with the intention of looking up some of the places she’d been to see what they looked like now. It promptly was buried by about 3,000 other pieces of paper. In the whirlwind of daily life with kids and a job and a spouse, Bird’s adventures would occasionally pop back into my head but would quickly be replaced by a grocery list or a trip to the post office.

Then March 2020 happened.

Try to remember what those early covid-days were like. There were only a couple of cases in the Pacific Northwest—and those were in assisted living facilities. The federal government insisted that they had it contained. We believed them enough to make plans.

In my part of the state, rumors about New York City hospitals starting to see cases were whispered. Then there was a gigantic outbreak in Westchester. Then there were portable morgues in place in Queens, makeshift quarantine beds in the Javits Center, and a staging area in Central Park. I was working on a college campus upstate, where we are close enough to feel connected to the city but have more cows than people. The college sent everyone home for an extra spring break week and fully expected to be back to normal by early April.

As we now all know, anything approaching normal was (and is) a long way from there.

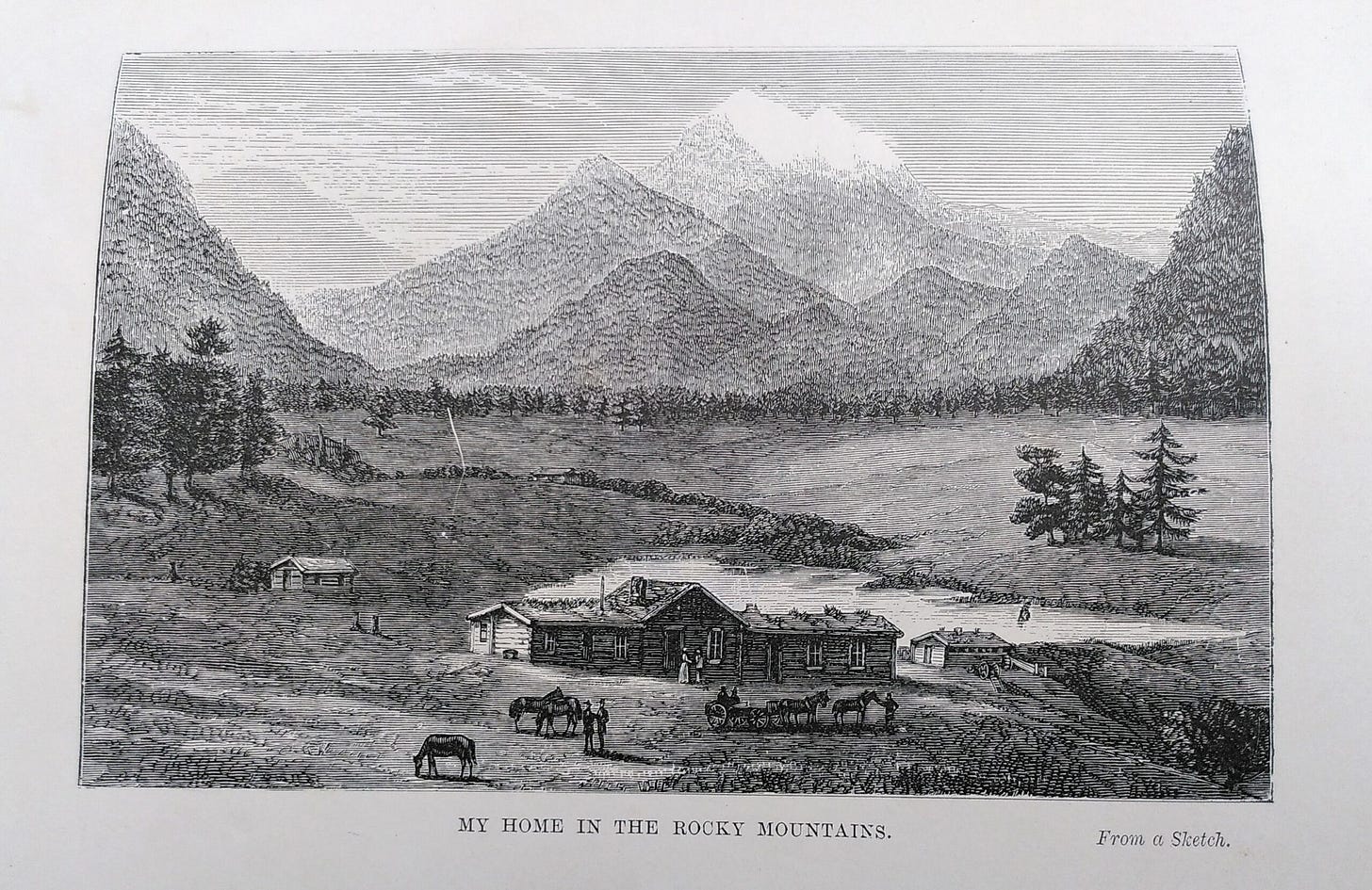

During the first few weeks of lock-down, I escaped into Unbeaten Tracks in Japan. When I finished that, I picked up A Lady’s Life in the Rocky Mountains, the book that Demers and Edith enjoyed. In it, Isabella travels the American West 1873. She started in San Francisco, took the train to Truckee, then rode a borrowed horse to Estes Park, past Colorado Springs, and around again. During that time, she also climbed Long’s Peak, worked as a cook/housekeeper when a global economic collapse froze her banks accounts, and met the love of her life (maybe), who would later be killed in a bar fight.

While I recognize most of the names of the places she saw, it feels like a foreign county. I’ve not traveled in the American West (again, other than the Denver airport) and don’t have a good sense of what the land outside of the cities is like. Given the separation between Bird’s time and mine, what she describes feels even more alien. For example, this reminder that public health crises are nothing new: those in the last stages of consumption1 would travel to Colorado to take in the thin air. Many, of course, would die before they got there. Which Isabella observed during a few day’s stay in a boarding house. The proprietess dealt with one or two dead strangers a month, laying them out on chairs in the front parlor before the authorities (such as they were) buried them outside of town.

Yes, the past is another country.2 Her Japan is not my Japan. Her Albany is not mine. I’d assume that her Estes Park would follow that pattern. That might be what makes Never in Hand work: the juxtaposition of then and now. So much has changed — we don’t take boats and trains anymore really, for starters — but so much about being human is exactly the same, even if ladies no longer wear corsets for anything but cosplay. This story is about those similarities and differences as well as all of the surprises waiting in the archives, like Mr Roessle, the Celery King. I’ve been exploring all of that in telling the story of a Victorian-era badass adventurer who would be absolutely appalled to be called one.

So where shall we go from here, dear reader? More about the rocky mountains? Japan? Where else she went? Her short-lived marriage? Do you want to choose the next part of her adventure you read? Or is it dealer’s choice?3

I have folders and tabs and more folders ready to go.

Some related (and not) links:

Because in my brain everything circles back to Isabella Bird, this piece about Mathelinda Nabugodi’s new book in the New York Times reminds me that a) Bird and her family were part of the anti-slavery movement and made a big deal out of forgoing sugar in their tee and b) everything connects.

If this is your thing,4 it’s time for 'Bama Rush.

I pushed to publish this installment of Bird’s story today mostly so that I can link to the brilliant Heather Cox Richardson’s celebration of Frances Perkins, who was another woman who could always find a way when there was no way. You could do worse than taking her attitude as inspiration.

John Green’s book on TB is a good one. Shame the disease is still around to be written about.

but the past and present never, ever fail to rhyme

I’m the dealer, btw.

It’s not my thing but I dabble.