The Bird Story, Part 5

Plus a couple o' links

If you are new1 or forgetful,2 the Bird story starts here.

What might be more surprising than Bird’s unusual vocation for a woman of her time3 would be how terrible her health was when she wasn’t traveling. She wound up taking her first trip to North America because her doctors ran out of better ideas. Bird was a sickly child, who failed to thrive despite her economic advantages. When she wasn’t in bed, she was laid out in the sun, which was seen as a potential wonder cure. Various concoctions were poured down her throat throughout her young life. A lot of those miracle elixirs only made her problems worse.

The most identifiable physical problem she had was a series of growths along her spine, which were operated on when she was in her early teens. But she also suffered from insomnia and what would likely be diagnosed as clinical depression now. As a young woman, her view of the world came from her bed, from books and the stories her mother told her and her sister. In her late teens, her doctors suggested a change of scenery might do her good. Her father handed her 100 pounds and told her to come back when the money ran out.

It’s hard to say what both her parents and her physicians imagined would happen. Did they expect her to thrive in the sea air? Or did they expect the coaches and trains to break her for good? And does it matter what they thought, given that we know how it turned out? She became known as the Samson abroad and the invalid at home. Travel saved her life—and allowed others to live vicariously through her, even now.

Cheryl Demers, who lives4 in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, discovered Bird’s Rocky Mountain stories in the early 1990s. She was newly divorced and was renting a basement apartment from “a deeply Christian gal who loved to read.” Demers asked for a book recommendation and her landlord suggested Bird’s book about the Colorado territory.

“I was in love with it. I was like, ‘This is the best book I've ever read, ever’ because Isabella Bird took me on her journey with her. I bought several copies for friends for birthdays and gave one to my mom. I wanted to share something I thought was gold,” Demers said.

Years later, Demers was a nursing home social worker. She became friends with Edith, who as in her late 80s and blind. Over dinner each night, Demers would read Bird’s book to Edith.

“The more we read, the more Edith was like, ‘I feel like I know this lady. I feel like I'm on her adventures,’” Demers said.

Edith was also an elder in the Chippewa Sioux Tribe. She loved reading about the history of the pioneers, because she always felt the native land had been taken from them.5 But Bird’s descriptions and attitude toward the native people in Colorado, which reflected the ideas of the late-Victorians and were less than kind, captured some essence of Edith’s experience.

“She shared with me how she had to go to Indian school,” Demers said. “She was taken away from her own family, her mom and her dad. She said her dad was not around much, and he drank. She had to stay in Indian school until she was married off."

Bird’s travelog unlocked Edith’s memories enough that she was willing to give Demers a glimpse into what life was like back then, which was its own reward. Mostly, though, Edith and Demers simply embraced Bird’s book.

“With Isabella, we fell in love with the part where the skunk goes under her home. Then when we got to the part about Mountain Jim,6 and she was like, "Can you read that over to me?’ And I did. And she said, ‘This is an adventure. This is romance.’"

The pair got through the story before Edith’s passing in 2010. But before her end came, Edith helped Demers plan her second wedding, which took place earlier that year.

“All of it was just a wonderful, wonderful experience and I wouldn't trade it for anything. I also think when I share this, Edith is with me in a different way,” Demers said. “Every time on my wedding anniversary, I think of Edith, because she had to help in my dress selection. When I think of her, and then I think of us reading the book together. When you're in a nursing home, reading carries you away. You get to go somewhere.”

That urge to go somewhere led me to Isabella Bird shortly after the pandemic lockdowns in early 2020. For me, however, the draw wasn’t her Rocky Mountain adventure, mostly because I haven’t spent much time in Colorado proper.7 Instead, it was Bird’s Japan journey that first pulled me in.

A few months before we all started to go more or less nowhere, I’d gotten to take the trip of a lifetime to Japan. I went with my Dad, who has long been a Japanophile. In short, it was a trip I’ll never forget. Yes, Japan is wonderful and stunning; but I spent ten days in a tiny ship’s cabin with my Dad, with whom I’ve not lived in more than 30 years. In Japan, it fully sunk in that my Dad still had the will to drink in every last shrine and garden and that his body would not let him because aging cannot be stopped.

For me, the trip was an opportunity to lean into how time passes so quickly while simultaneously being knocked on my ass by how odd and also familiar Japan is.

Shortly after we got back, I wandered over a mention of Bird’s Unbeaten Tracks in Japan, which was her travelog of a journey from Tokyo to Hokkaido in 1878. I’d never heard of her before that moment. But when I started reading (and once I got used to the rhythms of her writing), she felt like an old friend, if one who is more no-nonsense than anyone I know.

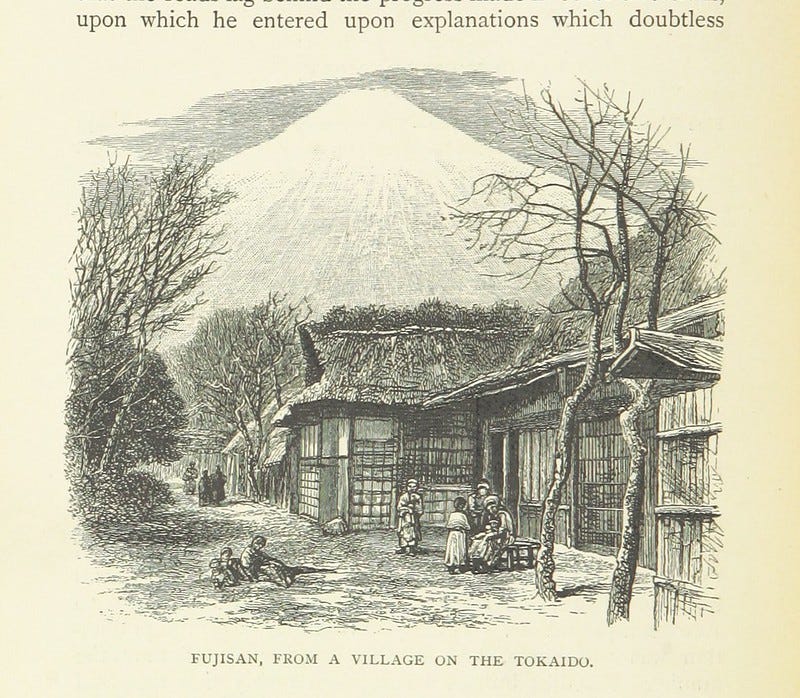

Bird first sees Japan from the water, as her ship pulls into Yokohama, the port town that feeds into Tokyo.8

“The day was soft and grey,” she begins, “with a little faint blue sky, and though the coast of Japan is much more prepossessing than most coasts, there were no startling surprises either of colour or form. Broken wooded ridges, deeply cleft, rise from the water’s edge, grey, deep-roofed villages cluster about the mouths of the ravines, and terraces of rice cultivation, bright with the greenness of English lawns, run up to a great height among dark masses of upland forest.”

And in that instant, I was back on that luxury cruise ship on the Inland sea, feeling the cool, damp air as the deck rocked under me. Our first morning was overcast. The blue-gray water met the blue-gray sky, except where is was broken by the pine-laden coast. The boat’s path was dotted with rocky islands, which seemed to be arranged by the volcanoes that birthed them in just the right places to provide a gasp-inducing composition. The view looked like it had been retouched to evoke wonder and awe. Instead, it was right out my window on a Tuesday.

A couple of links:

This remains one of my favorite museum-going experiences ever, which means that I’m going to have to get myself to Oakland, CA.

Trans people have always existed. Example #4002: 18th Century France.

I think this woman and Bird were of similar vibe.

Cherie Priest nails the current state of the publishing industry. (And buy her books!)

I dream of taking a ride with Bernd Maylander.

Hi! How did you get here?

Same!

Reminder: the time is the mid-1800s. The place is the U.K. but then all around the world.

I’ve lost touch with Demers, unfortunately. :(

I mean … fair.

we’ll get to him.

I’m assuming that the Denver airport is different from the state as a whole.

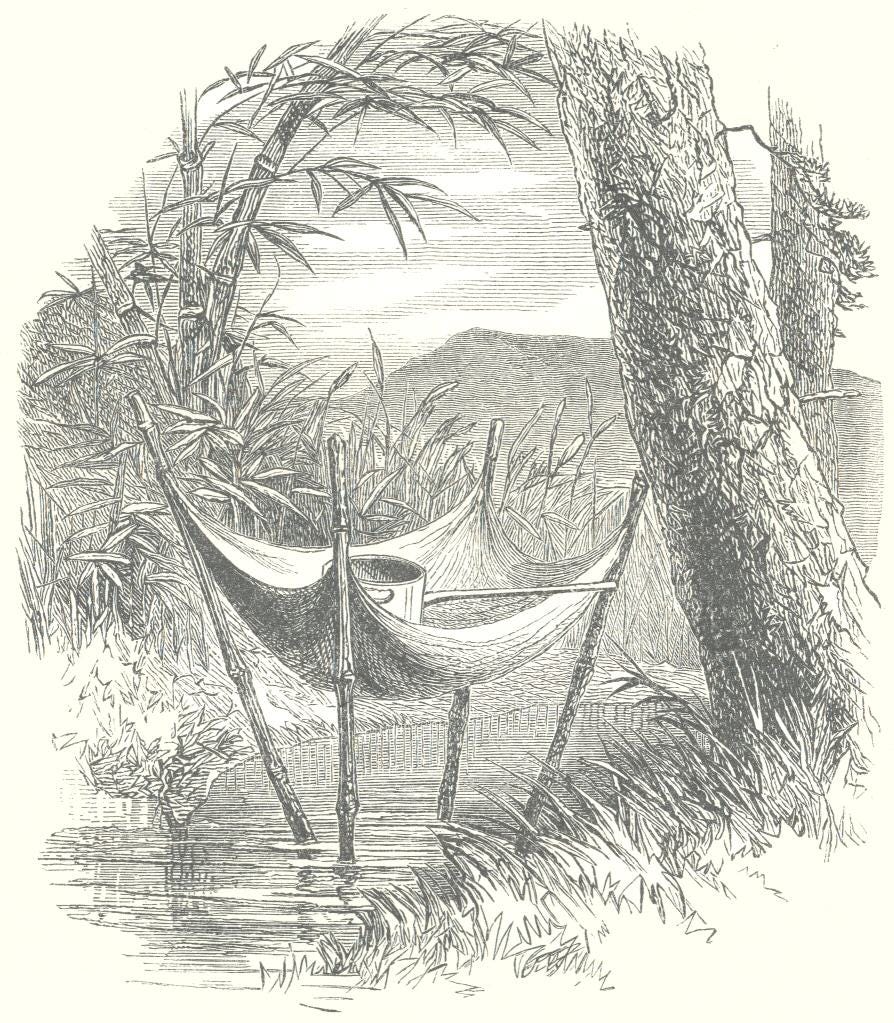

I’m going to put this here, because it’s one of the stories from her Japan book that proves that people will always behave like people, no matter when or where.

So it was custom at the time in rural Japan to commemorate the death of a loved one by suspending a piece of cloth over a pond or stream. You would come each day and pour a dipper-ful of water through the cloth. When the cloth had weakened enough that the dipper fell through, your time of mourning had ended.

Very sweet, yes.

However.

You could speed the whole process up by buying cloth that was already thinned in the middle. You could also pay someone to come each day and make the offering for you. While Bird doesn’t mention it outright, I strongly suspect you could also buy a heavier dipper.

Because of course you could.

Gladly went to read Bird Part 1. It's awesome to see a photo of Sil after all these years!!

Isn't the Oakland diorama thing wild??? I cannot WAIT to see the exhibit of that.