When we left off, Bird had just returned home from her first trip to North America and decided a return voyage was needed…

Bird’s second trip1 across the Atlantic was scheduled to last six months but took a year. The end goal was to add her boots-on-the-ground observations to a manuscript her father had mostly completed about religion in the U.S.

Instead, her observations were turned into a second book about America, one where she focused on explaining how these former colonies had changed since the revolution. Bird dug into our systems so that she could explain them to her British readers. What she diagnosed in 1853 — pre-Civil War, remember — are illnesses we are still attempting to cure more than 150 years later.

Kentucky was the first slave state Bird visited. Her first encounter with a slave stuck with her. On the street, she saw “a being created in the image of God, yet the bona fide property of his fellow-man. The first I saw was an African female, the slave of a lady from Florida, with a complexion as black as the law which held her in captivity.”

Bird and her family were strong abolitionists and opposed the trade in the British West Indies (so strongly, in fact, that her aunts refused to use sugar in their tea in protest.) Anti-slavery advocate William Wilberforce was both a relative and a friend of the family. Her anti-slavery stance grew out of her fully felt and deeply studied faith. According to a contemporary biographer, who was a friend-of-a-friend of Isabella, she “went to all the religious meetings, of whatever creed professed, and listened to no fewer than 130 sermons, some of them preached to Indians, to trappers, to negroes, and by negroes.”

Perhaps the service which moved her most was one in the African Baptist Church in Richmond. An “aged negro, called upon to pray, did so in such a manner, reverent, apt, and eloquent, with such perfect diction and accent and with such a fullness of thoughtful petition, that she burst into tears and declared afterwards that her religious life was quickened and strengthened forever by this beautiful prayer uttered by a slave.”

Bird’s objections are grounded in more than the sheer evilness of one person owning another person (which ought to be enough, of course), she also objects because creating an oppressed class of people is just a bad structure to build a country on. At that time, 3 million people were enslaved and 430,000 “colored persons, nominally free, but who occupy a social position of the lowest grade.”

That number will only increase to 6 million in 25 years and that will create “a population dangerous from numbers merely, but doubly, trebly so in their consciousness of oppression, and in the passions which may incite them to such a terrible revenge.”

This alone should be enough for America to do the right thing, both out of naked self-interest and in the eyes of God.

“America boasts of freedom, and of such a progress as the world has never seen before,” Bird wrote, “but while the tide of the Anglo-Saxon race rolls across her continent, and while we contemplate with pleasure a vast nation governed by by free institutions, and professing a pure faith, a hand, faintly seen at present, but destined ‘ere long to force itself upon the attention of all, points to the empires of a by-gone civilization, and shows that they had their periods in which to rise, flourish, and decay, and that slavery was the main cause of that decay.”

In another chapter she concludes, “The struggle between the advocates of freedom and slavery is now convulsing America…and appearances seem to indicate a prolonged and disastrous conflict between the North and the South.”

From a 2020 vantage point, we know how that turned out. Rather than devote our collective energy into reconstruction after the Civil War until the job was done, we chose instead to prop up our racist past over and over again with predictable results. In 2021, after a summer of protest and after an armed insurrection marched into the U.S. Capital in support of a white supremacist (among other things),2 Bird’s observation seems especially prescient. She could see what would happen long before we got here.

Bird’s travels through America and parts of Canada weren’t all devoted to pointing out injustice. Among other adventures, she spent a week in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she communed with the poet and other great thinkers of the day like James Russel Lowell, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Henry David Thoreau3.

(As you might have already figured out, Bird had no problem making her opinions known. Of Longfellow’s work she said, “Although it is very unequal and occasionally fantastic, and though in one of his greatest poems the English language appears to dance in chains in the hexameter, many of his shorter pieces well upwards from the heart, in a manner which is likely to ensure durable fame for their author.” Which is a great 19th century burn.)

Bird returned to England from her second trip to America at the end of April 1858. That very day, her father caught influenza and was dead by mid-May. Dora, Hennie, and Isabella grieved.

The work went on, however. She added to her father’s draft and Some account of the Great Religious Awakening now going on in the United States was published. Additionally, she wrote a ten episode travelogue for a magazine and a couple of pamphlets about abolition, a cause she would continue to fight for. With that, her own work became increasingly known. She was 25.

The remaining Birds moved to Edinburgh after their patriarch’s death. There, Isabella’s health declined. She threw her energy in to a charity working to relocate those who lived in the Outer Hebrides, where poverty and famine were increasing both human misery and mortality. She made a short trip to Canada in 1866 to see those islanders resettled. Then, that August, her mother died. Isabella was 34.

Years pass, as they do. Isabella and Henrietta stayed in Scotland and did their best to save those living in urban squalor. (Just a note: their idea of how to “save” people wouldn’t square well with what we’d do now. That is a conversation for later.) She helps get the Harris Tweed industry on its feet to provide jobs for crofters. She campaigns for clean, freely available water for Edinburgh’s poor so that they have more options than whisky. But it’s not enough.

“I feel as if my life were spent in the very ignoble occupation of taking care of myself, and that unless some disturbing influences arise I am in great danger of becoming perfectly encrusted with selfishness, and, like the hero of Romola, of living to make life agreeable and its path smooth to myself alone. Indeed, this summer I have made very painful discoveries on this subject and long for a cheerful intellect and self-denying spirit, which seeks not its own and pleaseth not itself,” Isabella wrote in her diary.

By 1872 and back in Britain, Isabella’s health has declined so much that she really doesn’t sleep but spends whole days in bed. Sources hint that she has a mental breakdown of some sort. And, as her doctors did before, they suggest she get on a boat and go somewhere.

By the time of Isabella’s death in 1904, she’ll have traveled to Australia, New Zealand, Hawaii, the American West, Japan, China, Hong Kong, Saigon, the Malay Peninsula, Kashmir, Tibet, Persia, Kurdistan, Seoul, and Morocco. Along the way, she’ll become a bestselling author, a nurse, and a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society. She’ll marry at 50 — and technically become “Isabella Bird Bishop,” although most who know her fail to use her married name. Some even call her husband John Bishop “Mr. Bird.”

A few years later, Mr. Bird will die despite traveling all over England and France to find a cure for his anemia. After going to college for nursing, Isabella will take up travel again. She’ll set-up and support hospitals in rural India. It won’t be easy, especially for a woman who doesn’t really get started until middle age. All of these things will be worth it, for her, for those who read her work, and for the communities who receive medical care.

More4 next time …

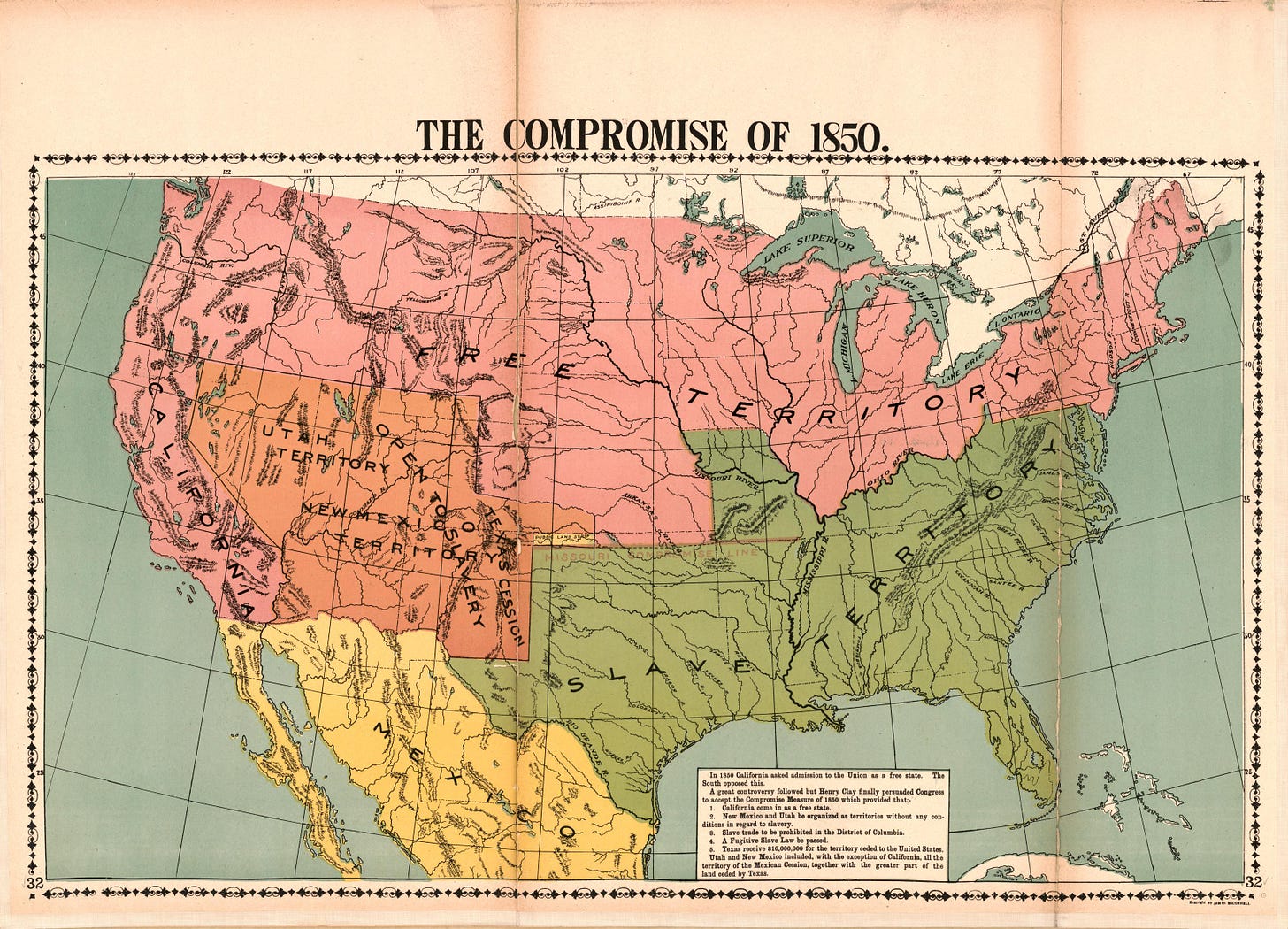

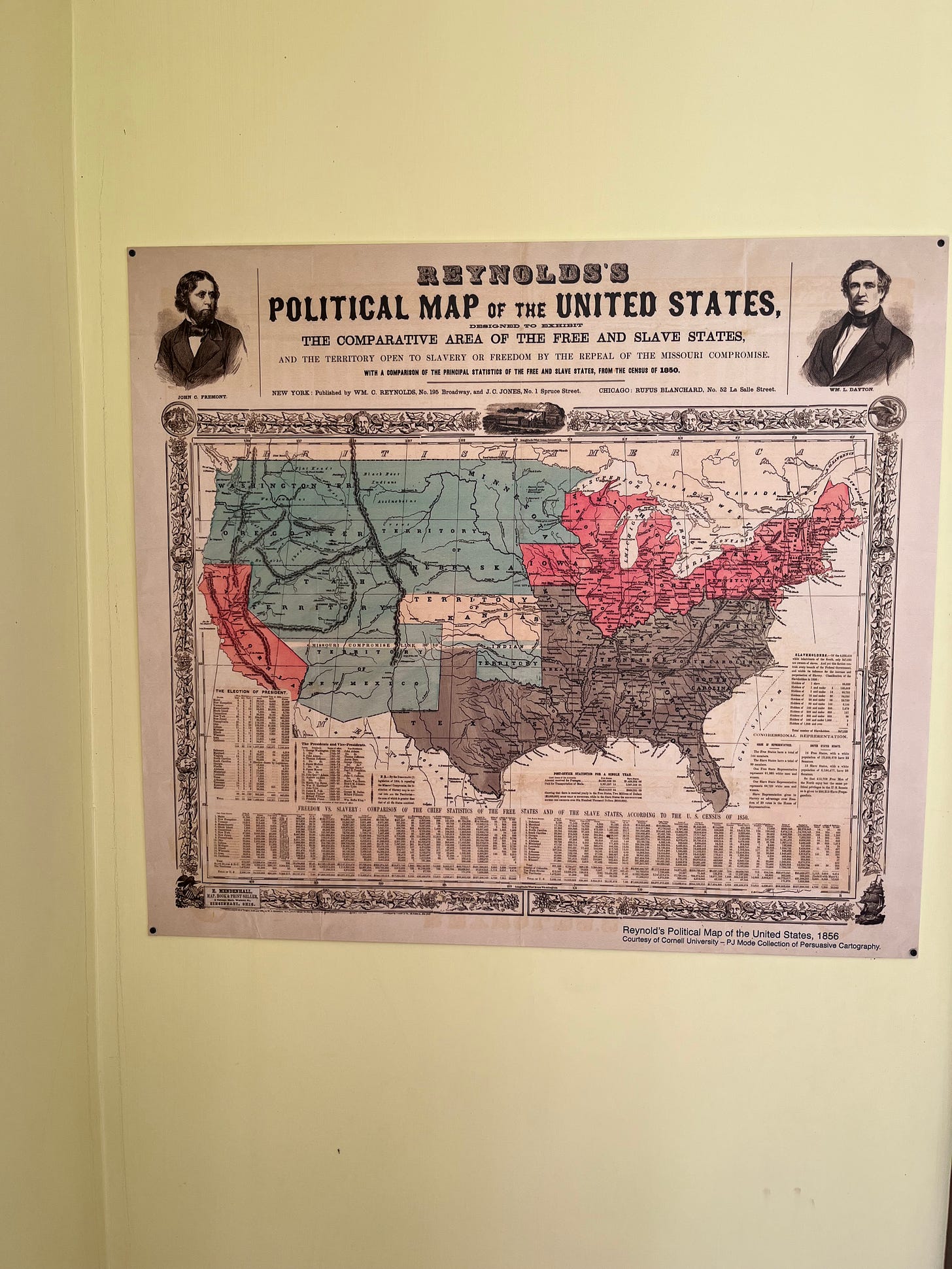

This aside is actually about the image above these words. Apparently, I can’t footnote a photo caption. Mentally move this there.

When I found this map on the googles, my brain knew I’d seen it before. Eventually it dawned on me: I’ve seen it at work at few million times.

The Fenimore Farm has Samuel Nelson’s office on its property. He hailed from Cooperstown and was a Supreme Court Justice from 1845-1872. What he’s most know for is his role in the Dred Scott decision, which essentially ruled that enslaved people weren’t actually people and couldn’t have rights. Scott, who’d been born in enslavement, had been living in free states for years but remained the property of his owner.

It’s one of the worst decisions in history, according the above informative signage and to this video.

(FWIW: I suspect there are worse decisions but Dred Scott is certainly in the top ten.)

Anyhoo, there’s a whole informative display in the building about Nelson. It doesn’t pull punches. And it also contains this map.

Fun fact—the headstone for Pamelia, one of Nelson’s daughters, is about 20 feet from the building.

The very much legal way that the museum acquired the headstones is its own story and this footnote is long enough.

TL;DR: Everything connects to everything else eventually and we’re all going to wind up with measles.

It was 2022 when I wrote this. It looked like a this chapter of our country’s history was behind us. SIGH.

Speaking of Cooperstown (sort of): her wagon ride through the Adirondacks to Albany she describes a moment “Occasionally the smoke of an Indian wigwam would rise in a thin blue cloud from among the dark foliage of the hemlock; and by the primitive habitation one of the aboriginal possessors of the soil might be seen, in tattered habiliments, cleaning a gun or repairing a bark canoe, scarcely deigning an apathetic glance at those whom the appliances of civilization and science had placed so immeasurably above him. Then a squaw, with a papoose strapped on her back, would peep at us from behind a tree; or a half-clothed urchin would pursue us for coppers, contrasting strangely from the majesty of Uncas, or the sublimity of Chingachgook, portraits which it is doubtful Cooper ever took from life.”

The Cooper is James Fenimore and she’s referencing 1826’s The Last of the Mohicans.

Another fun fact: You ca get a boat tour of Glimmerglass Lake on the Chief Uncas, which was originally built by Adolphus Busch, the beer guy, who used to summer in Cooperstown.

including the Celery King of Albany, NY.