The Bird Story, part 2

The beginning of the story is here.1

Isabella Bird was like a wild vine

stuck in a too-small pot.

She needed more room.

She had to get out.

She had to explore.

But petite Isabella,

pale Isabella,

proper Isabella

Was an unlikely candidate for adventure.

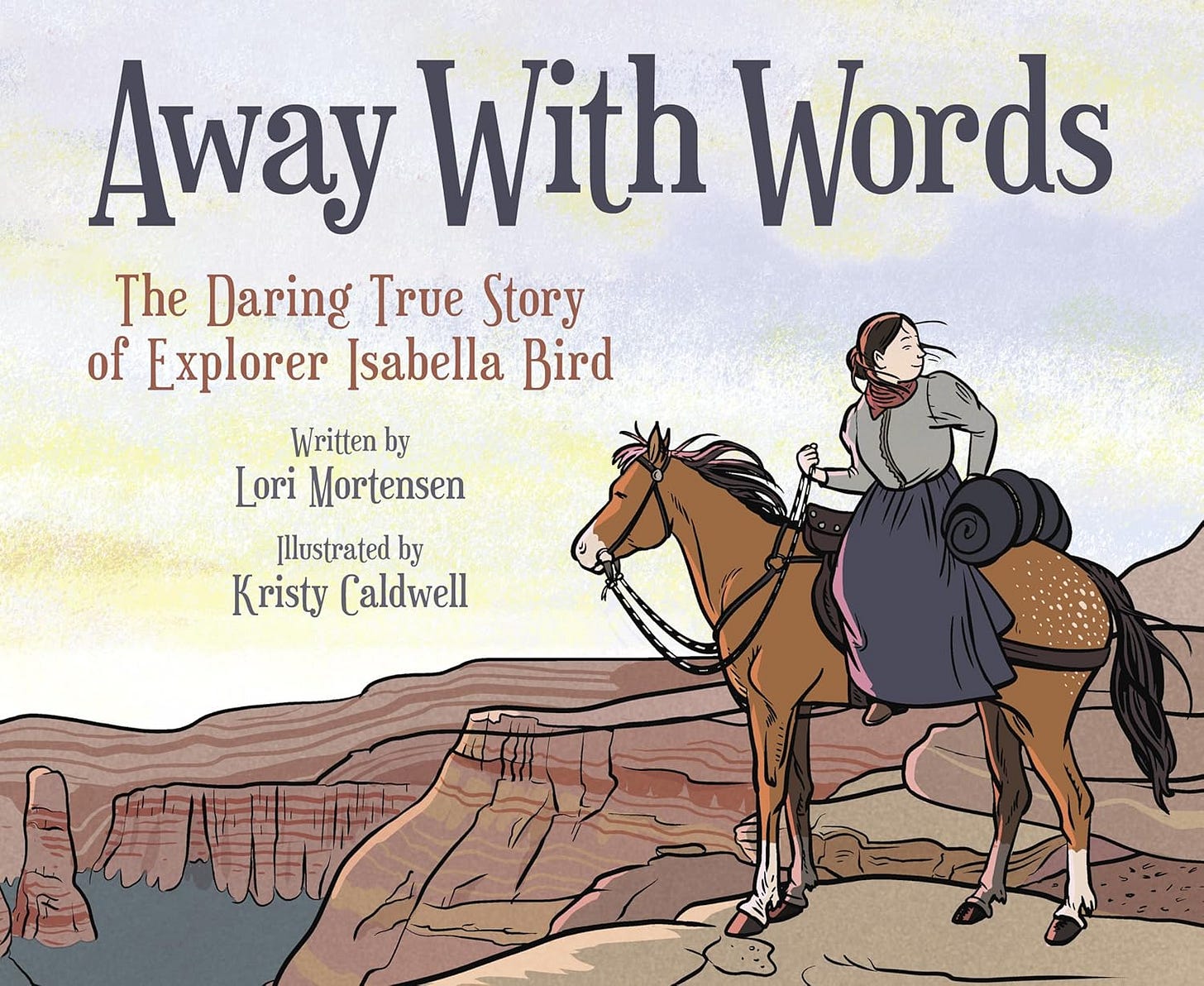

— Away with Words: the Daring Story of Isabella Bird (a book for kids) by Lori Mortensen and Kristy Caldwell

#

Isabella was born in Yorkshire to Edward Bird, a vicar in the Church of England in 1831. She was his first child with his second wife Dora. His first wife and child died in one of the many epidemics that swept through India while he was posted there. Remember: this was during the years when the sun never set upon the British Empire, especially in places they could colonize and exploit for cheap labor and material goods. It was what it was — and we will be reckoning with that for at least another century or two.

Three years later, Dora and Edward would welcome Henrietta — Hennie, as she’d become known — to their family. Hennie would thrive through all of the moves the family made from Yorkshire to Maidenhead to Cheshire to Birmingham. Isabella did not. She was a sickly kid, one prone to illness, pain, and insomnia. As an older teen, she had a tumor removed from her spine, which sounds like even more of a nightmare when you think about 1850s anesthesia. When she was in her early 20s, her doctor suggested she wear a steel mesh contraption to hold the weight of her head.

Rather than focus on what Isabella couldn’t do, her parents focused on what she could do. Both girls were given expansive educations — not just “expansive for the lesser sex,” mind. They were taught as if they were boys, with a full curriculum of Latin and logic and botany. Isabella shone in the academic sphere and had a pamphlet contrasting free trade and protectionism published when she was 16.

Isabella’s other strength was horseback riding. She was plunked on a horse as a toddler and grew into an accomplished horsewoman. Her world grew once she could see it from five feet up. And once she found a socially acceptable way to ride astride — women only rode sidesaddle at the time — she was able to see parts of the world where even men failed to tread.

The family moved frequently — and not because Edward Bird was an in-demand, beloved minister. He kept alienating his congregations because he was strict about the Sabbath. No commerce was to be done on the Lord’s holy day, he firmly believed, but his increasingly middle class parishioners disagreed. They kept the wheels of capitalism moving, especially in a large city like Birmingham, and had no time for Bird’s counsel otherwise.

It’s not like Father Bird had to work. Some of Isabella’s success is due to inherited wealth. It wasn’t castle-in-the-country money, mind, but it wasn’t one-step-from-the-workhouse either. They were comfortable enough to keep the sisters in tutors and saddles. Their parents were their most consistent teachers, with their father telling them about his time in India and instilling them a Jesuit-like method for asking questions about their world.

Their best educator, however, may have been their mother Dora, who was herself highly educated and the daughter of a well-known prebendary in the Church of England. “No one can teach now as my mother taught,” Isabella later said. “It was all so wonderfully interesting that we sat spellbound.”

All of their money and status couldn’t improve Isabella’s health. The spinal surgery wasn’t completely successful — and given that germ theory hadn’t yet been realized, it is a wonder the procedure didn’t kill her outright. Most of her days were spent lying in bed and, when the pain relented enough that she could focus, reading and dreaming about the world outside her bedroom.

At 22, she wasn’t sleeping, still in pain, and suffering from “lassitude.” Her doctors tried bloodletting and leeches, which (surprise) only made her weaker. Bird was prescribed laudanum, potassium bromide, and chlorodyne, which is a mix of opium and cannabis. Bird said drugs made her “more nervous than I have ever been and I cannot remember anything or read a book. These last few days I have felt shaking all over and oppressed with undefined terror.”

Despite all of the promises made by mid-19th century doctors and medicine (and just maybe because of all of them), Bird’s health remained terrible. Her doctors might have decided that there was little left to lose by suggesting that this headstrong and intelligent woman challenge herself with an adventure. Maybe a sea voyage would do you good, they suggested. Many upper middle class young women were taking the Grand Tour, where they would spend a year seeing the sites of the continent before settling down to domestic life. Perhaps that would help?

Isabella and her father decided that would be a great idea. But rather than go where everyone else was going, he gave her 100 pounds and sent her to North America’s East Coast, where she was to visit a cousin. She could see whatever sites tickled her fancy. When the money ran out, she was to come home. With that, everything moved from sepia-toned to technicolor.

Her first stop was Halifax, then on to Rock Island, Illinois, and Cincinnati. After a couple of delays because of a cholera epidemic in New York City, she finished the trip up with stops in Quebec and Prince Edward Island. Remember that this was the early days of a new nation — and that what would now take a couple of days by car was a seven month long ordeal on boats, trains, and horses. It was not a journey you’d expect an ill person to do well with.

She loved it. The insomnia stuck around but all of her other symptoms vanished.

While it was unusual for a young woman to travel alone at the time — most of the ladies on the Grand Tour2 went as a pack rather than solo — Isabella’s way was smoothed by letters of introduction her family provided, her status as an outsider in this country, and her relative wealth. Her life at home was constrained by what English society expected her to be; here, however, she was given the freedom to be whomever she chose, within reason. “She had no concerns about personal safety when unaccompanied by friends or relatives,” Clarence Strowbridge writes in a new introduction to her first book. Isabella backs that up in her own words: “a lady, no matter what her youth or attractions might be, could travel alone through every state in the Union, and never meet with anything but attention and respect.”

Which might not have been true for an American woman of her age at the time, or for one who had less money, but status worked in Isabella’s favor. In all of her books, she tends to brush over any moments where she is overcome by other people’s expectations of her. Her daily life on the trail might have been full of all of the biases against her sex a modern set of eyes would see but was the water she swam in.

That’s not to say she never had a moment’s discomfort or confusion. On the sail over, her cabin-mate was a drunk English atheist who threatened to throw Isabella’s Bible overboard. Her luggage tickets were stolen out of her pocket on a train to Chicago. On a sail up the St. Lawrence river, she met a man who claimed to have murdered his wife and also was, incidentally, the King of Montreal.

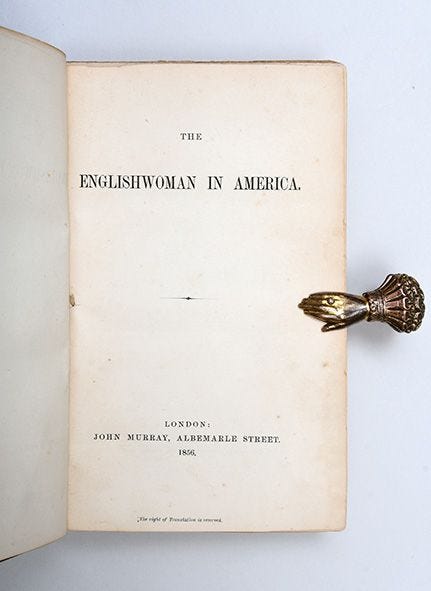

Once back home, she compiled her notes into what became her first book, The Englishwoman in America. It was published by John Murray, whose publishing house would go on to print all of her books. As exciting as that was, Bird’s health began to decline again in Britain. Her father suggested she travel back to America to learn about our religious practices. So she did.

… to be continued.

In the 19th century, it was fashionable for young men of a certain class to travel throughout Europe as an educational pilgrimage and usually in the company of a tutor. As the century progressed, a few young women lit out for the continent as well but always with a chaperone.